Snider conversion and Magdala

The adoption of the Snider, and its use in an early battle

By Fred Wilkinson

Origins of the Snider

By the mid 19th century the British Government maintained an army, a navy and a large volunteer rifle movement, in addition to several Colonial Forces. The equipping of these units was a major commitment. The period was one of technical change and the concept of breech-loading firearms was widespread. Several potential enemies were equipping or, had already equipped, their forces with rifles that used some form of a breech-loading system. Virtually all British military firearms were muzzle- loading which meant that they were slow to load and consequently less effective than the new breech-loaders. A few capping- breech loading weapons had been issued to some cavalry units but were not thought to be entirely suitable.

The rifle was still a comparatively new weapon in the British army and the vast majority of troops were armed with muzzle-loading muskets. Until the late 1830’s these muskets had been flintlock weapons but the army had recently converted many to the new-fangled percussion cap system. Until the advent of the Brunswick rifle of 1836 the majority of firearms were smooth-bore but the Brunswick barrel was fashioned with two deep grooves which imparted a spin to the bullet. This may have improved accuracy but loading was not easy and the Brunswick rifle was never popular. It was the adoption of the Enfield rifle in 1851 that made the majority of troops familiar with the rifle. It was a reliable, accurate weapon and it was this rifle that would eventually be converted to the Snider system.

Early muzzle-loading rifles utilised a paper cartridge containing a charge of black powder and a lead bullet. The paper case was torn open at one end and the powder poured down the barrel, followed by the paper, which acted as a wad, and then by the ball. The whole charge was rammed down into the breech using a wooden or steel ramrod. A percussion cap was then placed on the nipple, the hammer cocked and the rifle was ready to fire. The process took time and a well trained soldier might get off two or three shots a minute.

In designing a breech-loading weapon there are two main problems; one is the method of physically placing the powder and ball into the breech; there had been early systems that managed this quite well but they tended to be rather complicated and not a little dangerous. The development of the percussion cap had simplified ignition and by the mid 19th century metal- cased cartridges incorporating powder, missile and the ignition system had been developed. Patented by Berdan in the USA and Boxer in Britain, metal cased cartridges were becoming the norm.

The second problem was to devise a system that allowed the cartridge to be inserted at the breech and then ensured that once it was in position the opening was tightly closed. The closure had to be as tight as possible,else when the round was fired there would be an escape of gas and detritus that could make shooting the weapon uncomfortable and dangerous for the user. Obturation, or the leakage of gas and debris, was a problem that bedevilled many of the early breech-loading weapons.

Since it was obvious that breech-loading was the future, governments were faced with a difficult decision. Should they adopt a brand-new weapon which would be expensive, or could they find a method of adapting the muzzle-loading weapons to the new system? For the British military the problem was to discover whether there was a reliable, affordable way by which the current stock of muzzle- loading Enfield rifles might be adapted to use the new technology? When faced with this problem the Government adopted the time- honoured system of setting up a committee which was told to explore the possibilities.

The government collected together a number of experienced army officers to consider first of all whether the infantry should all be armed with breech-loaders. The Committee first met on 27th June 1864 and evidence was taken from its members who generally advocated their personal choice of breech-loading systems. On 30th June 1864 a second meeting was held and a current system, just adopted by the French, the needle gun of the Prussians, was discussed. On 5th July there was another meeting and on 11th July the Committee presented their conclusion that all the infantry should be armed with breech-loading rifles. There was no recommendation as to which form of breech-loading should be adopted.

The report also expressed a strong opinion that, because it was quicker and simpler to fire a breech-loading weapon this could lead to a waste of ammunition which was a valid comment. This point was made in emphatic, forthright terms by an officer of the Royal Artillery writing a series of articles in the Technical Educator . He wrote: “Many good soldiers and experienced officers declare that if you gave a soldier a gun which he could load very quickly he would expend all his ammunition before he came within effective fighting range. It may be admitted that breech-loaders are open to this objection although not to anything like the extent commonly supposed and the objection is one that can be remedied by discipline and an effective, careful training. The practice of the Prussians is an example of this. Here we have a nation that really understands the breechloader, which is properly trained in its use and in the economical expenditure of ammunition and the results that we have seen in two great wars. (He is probably referring to the defeat of Austria in 1866 and France in 1870.) On the other hand we have the excitable, and if we may be permitted to add, badly trained, ill drilled, ill disciplined French soldier blazing away any number of metres away from the enemy and running out of cartridges early in the day.” The committee took the point and very sensibly stressed that ammunition supplies would certainly need to be considered.

The Secretary of State accepted their conclusions and indicated that the next step was to look at the possibility of a stop-gap system, a conversion by which present weapons could be adapted to the new concept. He asked the Ordnance Committee to look around and find a method that would be quick to use, efficient and cheap; the cost to be no more than £1 per rifle. Another condition was that the new weapon was to be equal in performance to what it was prior to conversion. In view of the planned change of systems it was ordered that production of the old percussion Enfield rifle should be stopped as soon as possible.

Notice was given inviting gun-makers to submit for approval any system that they thought could meet these conditions. Each applicant was asked to submit six examples of their weapon plus a thousand rounds of suitable ammunition for which each would be paid £20 to cover their costs. In all some 47 arms were submitted and examined by the group, and of these nine were considered suitable for testing. Two were later eliminated and the final selection of seven gun-makers was each given six Enfield rifles (One, Shepard, was given 12 as he offered two versions) and each was allowed two months in which to convert the supplied weapons for testing.

Those finally chosen were:

a) Mont Storm, using a skin cartridge with a swivel chamber

b) Green, using a plunger; a chamber was fitted at rear of the barrel with access closed after loading in the cartridge

c) Wesley Richards, of monkey- tail fame; he was not very keen on the concept of conversion

d) Joslyn USA, who said that he could not get the conversion done in this country

e) Richards, who did not like the idea of conversion

f) Shepard, using metallic cartridges

g) Shepard, using service cap ammunition

h) Snider

i) Royal Small Arms Factory, using a special cartridge but this was withdrawn

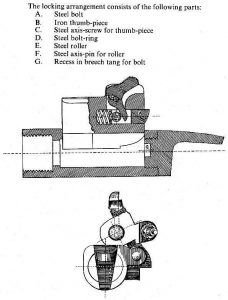

The Snider conversion consisted of cutting off two and a half inches at the breech end of the Enfield rifle barrel and replacing the missing part with a section of ‘half-barrel’ fitted with a vertically pivoting, longitudinal block. This block was lifted to allow access directly into the breech so that a cartridge could be inserted; the block was then lowered and held firmly in position.

Snider action

The block was fitted with an angled firing pin that was struck by the percussion hammer so as to detonate the primer in the base of the cartridge, and the shot was fired. The block was then lifted and at the same time slid back engaging with the rim of the empty case to eject it. The action was simple, robust and required no great technical skill in handling.

The approved models were then set up in fixed rests and then submitted to a battery of tests. One was to establish the rapidity of fire and discover the average time needed to fire twenty shots when the cartridges were set out ready for loading:

- Mont Storm’s system averaged 3 mins 1 sec

- Westley Richards averaged 3min 29sec

- Wilson’s 2 mins 44secs

- Green’s 2 min 26sec

- Snider 2mins 46 secs

- The service Enfield 6 min 52secs

Durability tests involving non-cleaning and exposure to the weather were also carried out. In addition to the above mentioned tests the action was also subjected to several reliability tests including being filled with sand and water. It was fired 500 times without cleaning and Greener reports that 30,000 rounds were fired from one rifle without any problems.

It was decided that the conditions of an accuracy test varied so much that a true comparison was deemed valueless. However one point was noted and that was that at a range of 500 yards the percussion Enfield had a mean deviation of 1.64 feet whilst the Snider had one of 5 feet.

When the tested rifles were removed from their rests several were found to have broken stocks due to some of the wood having been removed in order to accept the modification. The Westley Richards and the Snider were found to be strongest.

The Committee reported that at ranges of 500 and 800 yards no rifle was as accurate as the Enfield was at 500 yards but that the Snider was easy to use and the stock of the original Enfield rifle was very strong since no wood had to be removed to accommodate the action. The Snider had done very well but its cartridge was weak and was the cause of bad shooting.

Penetration tests were next on the list with bullets fired at stacks of planks:

- Westley Richards pierced 16 planks of ¾ inch.

- Storm 11 planks of ¾ inch.

- Wilson and Snider 11 planks

- Green 10 planks of ½ inch.

The conclusions of the committee were that only Westley Richard was as accurate as the service Enfield, and that the Snider was the only rifle well adapted for the use of cartridges incorporating their own ignition. One slight problem was noted in that for the fitting of the Snider screw it had to be brazed back on to the barrel and this involved heating the barrel. This might affect the metallic quality of the barrel; Snider promised to address this.

A second rapidity test was carried out, but this time the firing was to be the same as in action i.e. taking cartridges from a pouch. The results were:

- Snider 2 m 35 s (that included one slight jam)

- Green 3m 18s

- Storm 4m 23 s

- Wilson 4m 34s

- Westley Richards 4m 44s

- Enfield 7m 20 s

The sum result was that the committee considered the Snider to be the most promising. Despite this recommendation the Secretary of State favoured the Mont Storm system since it had the advantage that it could be loaded from the muzzle using standard ammunition or via the breech using a skin cartridge. On 16th Sept. 1865 this pattern was approved and 3000 rifles were ordered to be converted to Mont Storm.

Problems with the Snider system were attributed mostly to the cartridge rather than the action. In October Colonel Boxer, the inventor of the British cartridge, reported that he had devised a cartridge for the Snider Enfield that gave better accuracy than the Enfield. The body was of brown paper and thin sheet brass rolled loose and glued at the edge and had a bullet of 520 grains .573 diameter (Appendix 1). In November the Enfield factory was asked if it could produce a similar, superior, cartridge to the Mont Storm. In December the factory reported that the Mont Storm skin cartridge was proving to be unsatisfactory. Although a contract for 1000 converted Mont Storms was signed by Feb 1866 only 900 had been completed and only 66 had been received. Those delivered proved defective with burst barrels so the Secretary of State ordered that the contract be suspended.

In December Enfield was told to prepare sealed patterns of the Snider Enfield, and ten rifles were to be converted and 10,000 cartridges prepared. The sealed pattern weapons were supplied to gunmakers to serve as the standard production model. By March/April 1866 Snider were ready for testing and the new cartridge with a 480 grain bullet tests showed a 30% increase in accuracy over the old Enfield, penetration was as good, and 15 shots a minute were possible. In view of these results the Snider conversion was approved in May 1866 with an order for 20,000, and by July sealed issues were being supplied to contractors.

The inventor Jacob Snider (1811 – 1866) was an American who sadly gained little from his system, dying in poverty in England before receiving any money from the government. He took out several patents dealing with the basic principle of his system. The first was patent No 2471 of 5th November 1864, but the one most directly related to the conversion of muzzle-loading to breech-loading was patent No 2275 of 5th September 1865 and No 83 of 29th January 1866 when he is recorded as living in Lambs Conduit St., Holborn. On 22nd January he introduced another change and mentions the screw fitting for the barrel and he is then Jacob Snider Jnr of Sullivan County Penn USA now living in the Strand, London. In all he had six patents. The conversion program was extended to Naval rifles and others as well as carbines. Adoption was formally approved on 18 Sept 1866 and 4000 with 90 rounds each were set aside for a planned expedition…

Production went ahead and there were some problems often with the cartridge and there were reports of the block blowing open on rare occasions, but it was basically a success. The Naval rifle and carbines were also included in the conversion programme. As with all developments there were modifications and variants, and there were five marks of the long rifle:

- Mark 1 was for the original cartridge made by Pottet of France

- Mark II was modified for the new Boxer cartridge

- Mark II* was manufactured for the Boxer cartridge

- Mark II** had a changed breech block designed to strengthen it

- Mark III was a Snider rifle, not a converted Enfield, with a steel barrel and a locking catch.

The British Army at the time of the Snider

One great virtue of the Snider system was its simplicity of use. This was an important point for the men of the British Army of the mid 19th century as it was thought that the majority of the troops were unlikely to master any complicated system.

An article published in Chambers Journal in April 1862 detailed facts about who and why men enlisted. The article pointed out that whereas Europe had some form of conscription, the British soldier was almost always a volunteer. In Russia there were 14 soldiers for every 10,000 of the population – in Britain it was 8 per 10,000. On the other hand the cost of each Russian soldier was £13 per annum whilst in Britain it was a surprising £52. In the one hundred line regiments of the British army there were approximately 120,000 “common soldiers”, as he calls them. The writer stated the vast majority were from the lower classes or as he calls them “loose fish”. Of 73,000 men 2,000 have a fair knowledge of the three Rs, 20,000 could neither read nor write, and 13,000 could read but not write.

Why did men enlist? The author said some were patriots, but very few; some longed for adventure, but the vast majority joined for one reason only – poverty. On joining, a volunteer received a bounty and then a daily pay, and once attested he was admitted and to leave would make him a deserter. One third of those trying to enlist were rejected on health grounds. The majority were husbandmen or labourers, then came artisans, and the smallest group was that of shop men or clerks who were generally thought to be the more intelligent. The majority of all soldiers came from Ireland where there was great poverty.

There was a vast chasm between officers and the men, and NCOs felt no desire to accept a commission and become an officer. In the Crimean War it is reported that fifteen sergeants refused the offer of a commission in the Guards. They knew that they would be shunned by the regular officers and resented by the troops. This was the army now being equipped with the new Snider rifle, and this was the army that was to use it in action for the first time.

The Snider’s first use

Far away in darkest Africa a chain of events was to lead to a reluctant but carefully planned campaign against a very special Abyssinian. The instigator was a very remarkable man named Kasa born in 1818; details of his early life are vague as he came from a very humble family but had received quite a good education at a monastery school… He was a Christian with a hatred of the Muslims. Early in his life he was little more than a leader of a group of bandits but gradually he acquired power and married into the royal family until he virtually reigned supreme. He then took upon himself the title of Emperor Theodore.

He was an outstanding warrior and at first had a very good relationship with Europeans, and increasing unrest among his subjects made him realise that he needed modern weapons, especially artillery, and he was anxious to encourage Western technicians to come to Abyssinia. In England a Charles Cameron was appointed as British Consul to Theodore and visited him bearing a gift of pistols and a rifle from Queen Victoria; much to Theodore’s delight. Cameron was sent back to England with a message of good will for the queen. The letter reached London’s Foreign Office early in 1863 but no action was taken and no reply was sent. Theodore sent a similar letter to the French Government.

Meanwhile Theodore had been angered by some critical reports of his behaviour, written and published by a missionary. Furious he ordered that the author, Stern, and a companion should be put in chains; a common form of Abyssinian punishment. In 1864 another messenger arrived from England but still without a reply to the Emperor’s letter. The French had sent his letter back unopened. Theodore saw these as direct insults and ordered Cameron and other Europeans to be chained, and the group was sent to Theodore’s main headquarters. This was situated on a plateau at the top of a minor mountain known as the Magdala. The prisoners were sometimes ill–treated and feared death but at other times were allowed reasonable comfort. However Cameron had managed to get word of their condition back to London.

The thought of a servant of the Empire in chains caused uproar in London and efforts to settle the matter were put in motion. Various emissaries were sent and all seemed to be going well and a few technicians were encouraged to go to Abyssinia. But Theodore was unpredictable and it all went wrong, and all the messengers and Cameron’s group were confined yet again.

Requests or demands for the prisoners’ relief were ignored and London eventually conclude that all diplomatic efforts were likely to be in vain and a military solution might be required. In April 1867 one last effort was made and another messenger was sent, and a three month deadline set for the prisoners’ relief. Theodore refused to release his prisoners.

Serious thought was now given to a military campaign to free the prisoners and it was decided to use troops from India. Lt. General Sir Robert Napier was given command and 4000 Snider rifles were sent to India. A force of cavalry, artillery, engineers and infantry was organised with the majority being Indian troops but some English regiments were involved. Shipping was organised and thousands of mules and muleteers enrolled (figure 2) husbandsmen.

{ When the expedition was announced there were numerous suggestions from “experts” as to how the troops should be equipped. This uniform idea was one such and although a little bizarre does at least recognise that tropical conditions called for light clothing.}

Reconnaissance of the country was carried out, suitable landing sites chosen and the first disembarkations took place early in October 1867 and contact was established with local tribes, most of which were hostile to Theodore. One regiment, the 33rd Regiment of Foot (The Duke of Wellington’s) was to play a prominent role and was one of the few units to arrive still armed with the old muzzle loaders. They were issued with Sniders and quickly learnt to use them. The terrain was horrendous with mountains, gorges and rivers to cross and over which artillery and rocket were to be transported. The demands on the troops were excessive with often only a few miles being achieved in a day. There was trouble with some of the troops; the 33rd, mostly Irish, got into a state of near mutiny over some of their comments about the expedition.

Eventually the high massif with the Headquarters of Theodore on the plateau top was reached. Battle was joined at Arogi, flat ground at the base of the Magdala. Lines were hastily drawn up facing some thousands of Theodore’s soldiers. They began to move forward and the British stood firm and watched the enemy advance. At about 250 yards the command to fire was given and the first volley downed hundreds. The Abyssinians now expected the firing to ease as the troops took time to reload their old muzzle-loaders, but now the Snider came into its own and volley after volley was poured into the advancing warriors. Artillery and rocket fire was also directed against them and after about three hours of battle it was over with probably 2000 Abyssinian dead against some twenty British wounded. It is estimated that one regiment, The King’s Own, fired some 10,200 rounds estimated at twenty per rifle.

Theodore still refused to comply with requests to surrender but did release the prisoners, over fifty of them, who were allowed to come down to the British camp. Napier was in some dilemma and there was some doubt as whether, now the prisoners were free, the campaign was over? He decided that until Theodore surrendered he had no option but to continue, and on 13th April1868 an attack on his base was ordered. This involved hand to hand combat as troops fought their way up the pathways to the top. Eventually, largely due to men of the 33rd, the summit was taken and the battle was over. This was the last occasion on which regimental colours were carried into battle by an Ensign Wynter, who signalled victory by waving the flag. Theodore was found dead, apparently having committed suicide using one of the pistols sent to him by Queen Victoria. It is reported that the troops indulged in a period of looting but the campaign was over and a complete withdrawal was carried out.

Back in London the victory was celebrated, a campaign medal issued to serving troops and Napier was feted. Faith in the Snider had been justified and it was to remain in service for many years, especially with some of the Colonial troops. In honour of the events a special piece of music was composed and sold for four shillings (roughly £10) a copy and as an example of Imperial Pride probably sold well.

{ A Victorian music cover published in the wake of the campaign and typical of the public’s attitude to the battle with glory and pride in the troops. (10.5 ins by 13.5 ins.)}

Further reading

- For a full and exhaustive account of the introduction and use of the Snider rifle:- A Treatise on the Snider rifle the British soldier’s firearm 1866-c1880 by Ian Skennerton 1980

- The March to Magdala:- Frederick Myatt London 1970

- The Barefoot Emperor:- Philp Marsden London 2007

- Royal Armouries Yearbook Vol 4 1999:- contains an article on a sword presented to Major-General Sinclair R.A.M.C. by Queen Victoria. Sinclair was surgeon to the 33rd Regiment of Foot and went to Abyssinia with them. The sword (IX.1291), described as belonging to Theodore, is in fact a mediocre quality German hunting sword in poor condition but no doubt came back to England with the loot from the Magdala.

Appendix:

The Boxer Cartridge – transcribed from an article in The Technical Educator Weapons of War V by An Officer of the Royal Artillery.